How We Slept in the Stone Age – and Why We Often Sleep Worse Today

Imagine this: It’s night. No traffic noise, no phone charger glowing, no thousand‑euro mattress. Just a flickering fire, the smell of freshly burned grass – and somewhere out in the dark, an animal rustles.

That’s pretty close to what a typical night for our ancestors might have looked like.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth: Chances are they slept better than we do today – despite having no mattresses, no orthopedic pillows, and definitely no sleep apps.

So how is that even possible? Let’s take a look back to a night 200 000 years ago.

The First “Mattress” in Human History

Archaeologists discovered in South Africa’s Border Cave the oldest known human sleeping places – about 200 000 years old. They were made of woven grasses laid on a layer of wood ash. Doesn’t sound super‑cozy. But the ash had a genius side effect: it kept insects away and acted as a natural disinfectant (Science).

Bonus Feature: When the grass bedding became flea-infested, people simply torched the mat, smoothed the sterile ash, and spread a fresh layer of grass on top – sustainable, fire-powered recycling. (earthdate.org)

A bit later – around 77 000 years ago – people in what is now South Africa even built fragrant beds: thick mats of sweet grasses and aromatic leaves from the Cryptocarya plant that repelled parasites (Science).

In other words: our ancestors had basically invented the first anti‑mite bedding.

Group Sleep Instead of Single Beds

We often picture early humans as lone hunters falling asleep next to their clubs. In reality, sleeping was a group activity.

Why? Simple: safety and warmth.

- Safety: If you sleep with ten others and one wakes up because a saber‑toothed tiger growls outside, it could save everyone’s life.

- Warmth: Body heat replaced hot‑water bottles – or central heating.

Researchers studying modern hunter‑gatherer groups like the Hadza in Tanzania found that someone was almost always awake – whether in the middle of the night or early morning (Proc. R. Soc. B). Like an in‑built night shift.

How Much Did They Sleep?

Here’s where it gets interesting:

Most traditional hunter‑gatherer groups alive today (like the Hadza or the San) sleep on average only 6 to 6.5 hours per night (Current Biology).

That’s less than the “golden” 8 hours we hear so often – and yet they report feeling more rested.

The trick: They didn’t always sleep straight through. Short daytime naps and brief waking periods at night were totally normal.

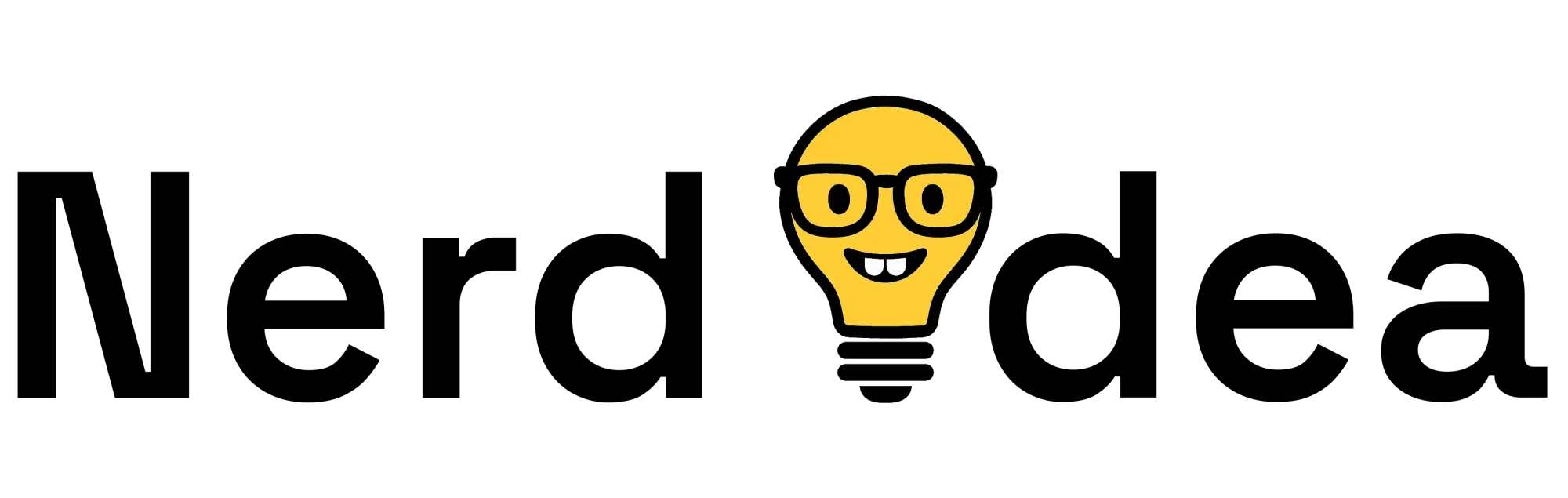

In medieval Europe, it was similar: historian A. Roger Ekirch found evidence of the so‑called “first” and “second sleep” – two phases of sleep separated by an hour of wakefulness around midnight (A. Roger Ekirch, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past).

And no, this wasn’t a bug, it was a feature: some used that hour to add wood to the fire, talk – or have sex.

And the Back Pain?

Now the tricky question: If they slept on piles of grass, didn’t they have constant back pain?

Surprisingly, the answer is: probably not more than we do – maybe even less.

Because:

- More movement – they walked, climbed, carried. Strong back muscles = well‑trained support.

- Less sitting – no desks, no cars.

- Natural posture? – A “J‑shaped” spine is often reported anecdotally in some indigenous groups (NPR), but imaging studies haven’t confirmed it; in fact, field research still finds significant low‑back‑pain prevalence – e.g. 45 % among rural Nigerian farmers (Rural Remote Health).

- No ultra‑thick mattresses – our modern “super‑soft clouds” can actually misalign the spine (Lancet).

So the truth lies somewhere between “they had steel spines” and “they suffered like us.”

Can You Sleep Like a Stone Age Human?

You probably won’t be lying in a cave tomorrow with your floor disinfected by wood ash (unless you’re really into hardcore time travel). But there are a few tricks you can try to get closer to that “Stone Age healthy” state.

1. Sleep Harder – But Not Too Hard

The big mattress question: Should you ditch your box spring and crash on a yoga mat?

Well, not so fast. Randomised trials show that medium‑firm mattresses best support the spine and reduce chronic low‑back pain compared with very hard or very soft surfaces (Lancet).

But many people report that a few nights on a futon, tatami, or even a thick blanket on the floor can be surprisingly comfortable. If you want to test it:

- Start with short power naps on the floor.

- Sleep on your side with slightly bent legs.

- If it hurts: stop. Your back isn’t an archaeological experiment.

2. Move Like a Hunter – Not Like an Office Chair

Maybe the most important point: our ancestors walked miles daily, squatted, climbed, carried – in short: they barely sat.

If you want to reduce back pain, you can’t buy a mattress upgrade – you need more movement.

- Walk instead of drive.

- Work standing up or try sitting on the floor.

- Try exercises like Animal Moves, yoga, or simply deep squats.

Fun fact: squatting is as normal in many cultures as chairs are for us – and it keeps hips and backs flexible.

3. Sleep the Way Nature Intended

Light

Stone Age humans didn’t have smartphone light blocking melatonin.

Today that means: put your phone away in the evening or use blue‑light filters. Just 30 minutes before bed can make a difference (PNAS).

Temperature

Sleep in cooler rooms (15 – 19 °C / 59 – 66 °F). Our ancestors slept outdoors or in cool caves – and that temperature triggers your body’s sleep mode (Sleep Med Rev).

Sound

They never slept in absolute silence – there was fire crackling, group snoring, wind. Maybe that’s why many sleep better today with white‑noise apps (Sleep Medicine).

Safety

Group sleeping meant safety. Today, even just feeling like you’re not alone can improve sleep – no wonder babies sleep better next to their parents.

4. Your Rhythm Can Be Flexible

If you wake up at night, that’s not automatically a sleep problem. Historically, it was normal to be awake for an hour after 3–4 hours of sleep.

You could use the time to read, meditate, or just rest quietly. Just don’t check your phone (unless you want to fall into a TikTok spiral at 3 a.m.).

So, What Now?

Sleep isn’t an 8‑hour luxury product. It’s a social, ecological, and biological puzzle that our ancestors solved with surprisingly simple tools: ash for insects, movement for the back, fire for warmth and community.

We, on the other hand, have memory foam, Netflix, and sleep trackers – and yet millions suffer from poor sleep.

Maybe the solution isn’t buying another “NASA foam high‑tech mattress,” but getting a bit closer to our roots: sleep firmer, move more, cut screens in the evening, and give your body what it’s been used to for 200 000 years.