The Can That Chills Itself — And Why It's Waiting for Its Moment

Imagine this:

It’s a sweltering summer day. You reach into your backpack. There, nestled between your sunscreen and your dignity (both slowly melting), is a can of your favorite drink — warm as bathwater. But this can is special. You press a button on its base, hear a satisfying PSSHT, and 90 seconds later you're sipping a frosty 8°C delight like you're being air-conditioned from the inside out.

This dream... is almost possible.

In fact, it’s been possible since before the iPhone existed. And yet, unless you’ve been in a top-secret beverage lab or watched a very specific episode of MythBusters, you’ve probably never seen a self-chilling can in real life.

So what's the deal?

Why don’t we live in a glorious future where every drink cools itself on command?

To answer that, we’ll need to dive into the strange world of thermodynamics, exploding cans, high-tech powdery rocks, Cold War-era salt chemistry, and... solar-powered origami.

Let’s go.

Act 1: How Hard Is It to Cool a Drink?

Let's start with the physics. Cooling a 330 ml can of something (say, soda, beer, or liquefied stress) from 25 °C to 8 °C takes about 23 kJ of energy removal. That's about half a modern smartphone’s battery — roughly 6.5 Wh, i.e., about 40–55% of a 12–15 Wh pack.

So no, it's not that much energy — the tricky part is how quickly you want to do it.

You could just put the can in your fridge and wait 90 minutes. Or your freezer, for 30 minutes, and risk a flavor-ruining soda explosion. But if you want your drink cold in 2–3 minutes, like a thirsty wizard, you're going to need engineering.

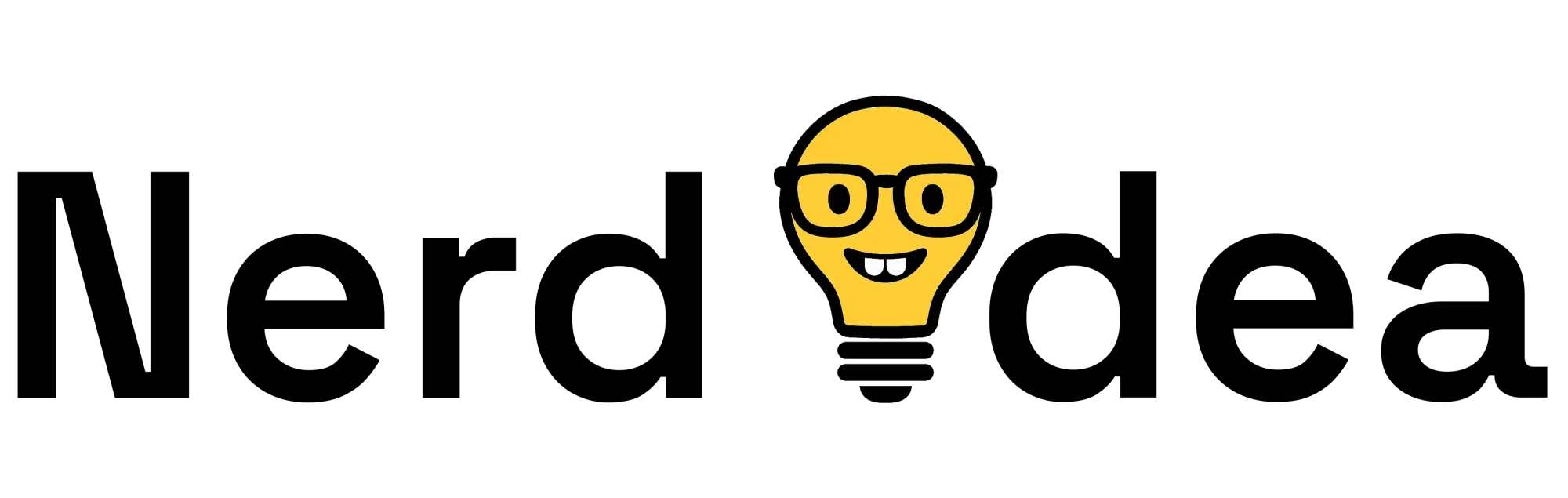

Act 2: Method #1 – Cooling by Releasing the Kraken (Gas Expansion)

Let’s say you take a tiny metal cartridge filled with a liquified gas — like CO₂, propane, or a fancy chemical with a name that sounds like a rejected droid from Star Wars (R1234yf). You open a tiny valve, and the pressurized gas explodes outward and evaporates, sucking heat out of its surroundings like an overcaffeinated dementor. (CO₂’s saturation/critical pressures near room temperature are very high, which drives robust flash cooling but demands stout hardware.)[1]

That’s exactly what a self-chilling gas-expansion can does. The cold gas flows through a coiled channel around the drink, absorbing heat as it goes, then vents out the bottom. It’s like a whipped-cream can spraying — but the chill goes into your soda, not your dessert.

The Pros:

- Fast. You can drop the drink temperature by 15–20°C in a few minutes.

- No electricity needed. Just press and chill.

- Sealed from the drink. No funky taste.

The Cons:

- The cartridge takes up space, so your "330 ml" drink might actually be more like 280 ml.

- You need high-pressure containers, especially for CO₂ — up to the tens of bar range at room temperature.

- You have to deal with flammability (hydrocarbons) or eco-regulations (some refrigerants). R1234yf, for example, is a low‑GWP refrigerant but classified A2L (mildly flammable).[2][3]

- It hisses loudly, can frost up, and requires a heat-exchanger spiral more complex than your kitchen plumbing.

Fun fact:

The Joseph Company once released the “Chill-Can”, a commercial self-cooling can. It used reclaimed CO₂ and was marketed for energy drinks and later a 7‑Eleven cold-brew pilot. It never took off, possibly because it cost more than the drink itself. (Or because consumers don't like mystery gas chambers near their mouths. Who knows.)[4][5]

Act 3: Method #2 – Sorption: The Can That Gets Hot to Get Cold

If the gas-expansion trick is like a miniature AC unit, then sorption cooling is like a science experiment smuggled inside your beverage.

Here’s the idea: You have a tiny vacuum chamber with some water and a hygroscopic powder (a.k.a. super-thirsty material like zeolite or silica gel). When you let the water into the vacuum, it flash-evaporates, stealing heat from its surroundings. Meanwhile, the vapor is sucked up by the powder, locking it away and keeping the pressure low so more water evaporates.

It’s like giving the water an existential crisis and then comforting it with therapy rocks.

Why this works:

- Evaporating water is really powerful: it can pull ~2,260 kJ/kg of heat (heat of vaporization at 100 °C — same order of magnitude at room temperature). So with just 10–15 g of water, you can cool an entire drink.[6]

- It’s completely safe: no high-pressure gases, no flammable materials.

- It’s quiet, has no moving parts, and the only byproducts are a warm can and your increased smugness.

The Challenges:

- The sorbent gets hot on the outside — you need cooling fins or a radiator sleeve. Typical free‑convection heat transfer to air is only on the order of 2–25 W/m²·K (often single digits to low teens), so you need lots of fin area or a bit more time.[7]

- It’s slow unless you use massive surface area or cheat with thermal storage (more on that later).

- The whole system adds 100–300 grams of extra mass. Great for weightlifting, less so for hiking.

- Once used, the sorbent is saturated. You can’t “un-chill” the can to reset it (unless you bake the rocks at 250 °C for an hour, which, let’s face it, you won’t).

Act 4: Method #3 – DIY Chemistry Set (Endothermic Salt Solution)

You know those instant cold packs you snap and shake when you sprain your dignity during a Zumba class? They work using a salt that absorbs heat when it dissolves in water. That’s called an endothermic process, and it’s the third way to chill a drink.

In a self-cooling can, the salt and water are stored separately. Press a button → the water floods the salt chamber → the temperature of the salty soup plummets → the can chills through a jacketed heat-exchanger.

Benefits:

- Dirt simple. Just mix salt and water.

- No pressure. No flammability. No rocks that need therapy.

- Materials are cheap and widely available.

Caveats:

- You need lots of material. To get ~23 kJ of cooling, you might end up with 150–250 g of water+salt depending on the formulation.

- The whole setup is single-use, and the leftover brine is gross, not to mention hard to recycle.

- In medical contexts, at least one study found some commercial chemical cold packs may provide insufficient total enthalpy change for treating hyperthermia.[8]

- If you go the stronger cooling route with ammonium nitrate, you get better performance—but also regulatory headaches and handling concerns; dissolving ammonium nitrate in water is a classic endothermic cold‑pack demo.[9]

So yes, you can cool a drink this way. But you'll also be carrying a small chemistry lab on your picnic, which may raise eyebrows at the airport.

Act 5: Which One Wins So Far?

Let’s recap:

| Method | Speed | Reuse? | Eco? | Safety | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas-expansion | ★★★★★ | No | Depends | Pressurized | Med |

| Sorption (zeolite) | ★★★☆☆ | No* | Yes (mostly) | Very safe | High |

| Salt-solution | ★★★☆☆ | No | Meh | Moderate | High |

- Sorption can become reusable with a home base station that regenerates the powder — cool idea, not common yet.

Act 6: Peltier Coolers — Electricity’s Least Efficient Magic Trick

Let’s say you want to cool a can using only electricity, no fluids, no powders, just solid-state physics.

You reach for a Peltier module, also known as a thermoelectric cooler.

Peltier devices are flat tiles of semiconductor material. When electricity flows through them, one side gets cold, the other gets hot. Sounds perfect, right?

Well…

Imagine trying to chill your drink by using a flamethrower on one side of a metal slab and hoping the other side gets cold enough to matter.

That’s kind of how a Peltier works. Typical real-world coefficients of performance in this temperature range are well below 1, which means a lot of waste heat to dump.[10][11]

Performance check:

-

To cool a 330 ml drink from 25 °C to 8 °C in 10 minutes, a typical Peltier unit would need:

- ~80–100 W of electrical power

- A heatsink big enough to cool a gaming laptop

- A battery about the size of a soda can itself

It’s like carrying a fridge just for one drink.

But! This tech is simple, has no moving parts, and is becoming lighter and cheaper. If you don’t need to chill fast, and you can plug into a power dock (like a picnic table or car dashboard), it can work just fine.

Act 7: Mini-Compressor Chillers — The Tiny Fridge Inside Your Hand

Now let’s get serious.

What if we actually build a fridge, but tiny?

That’s the idea behind miniature vapor-compression coolers — just like your kitchen fridge, but shrunk down to a brick-sized unit that clamps around your drink.

Inside is:

- A tiny compressor (about the size of a lipstick)

- A tiny expansion valve or capillary tube

- A coiled heat exchanger (cold side around the can)

- And a fan to get rid of the heat

When it kicks on, the cold-side loop cools the drink, and the hot side vents the heat, just like a normal fridge.

And guess what? It works.

With modern refrigerants like R1234yf (low global warming potential, mildly flammable), you can:

- Cool a can in 8–10 minutes

- Use only 20–30 W of electrical power

- Power it with a small battery (say, a 3S1P 18650 pack)

- Weigh under 1 kg, cooler included

This setup is 2–4× more efficient than Peltier devices — and probably your best bet for mobile, battery-powered self-chilling. (R1234yf’s A2L classification and very low GWP are documented by ASHRAE/industry sources.)[2:1][3:1][11:1]

Yes, it's real: You can already find portable can chillers using compressor tech, usually sold as picnic or car accessories. They’re not common, but they exist.[12]

Act 8: Solar-Powered Cooling — The Self-Chilling Picnic Table

So what if you don’t want to charge batteries or lug around power bricks? Could we use the sun to chill a drink?

Yes — but only if you go beyond the can.

Let’s do the math:

A typical PV panel (modern commercial modules ~20–23% efficient):

- 1 m² in peak sun (~1000 W/m²) → ~150–190 W usable after typical system losses

- A 0.3 m² fold‑out → ~45–60 W — enough to run an efficient mini‑compressor directly in bright sun

(PVWatts uses a default 14% system loss assumption; recent commercial c‑Si module efficiencies are reported around the low‑20% range.)[13][14]

Which means:

- With a fold‑out panel ~0.3 m² (like a trifold A4‑sized unit), you can absolutely power a mini‑compressor cooler directly in the sun.

- Add a small battery (20–40 Wh), and you can buffer the energy for use under clouds or mild shade.

You’ll want:

- A mini-compressor chiller ring

- Foldable PV wings that clip around the base (imagine a Pokémon evolving into a satellite dish)

- A small lithium battery for buffering and startup current

- An MPPT controller to keep the power flowing efficiently

In bright sun, you can chill a can in 10–15 minutes with zero emissions, no outlets, and a futuristic MacGyver-on-vacation vibe.

Just don’t try this on a rainy day unless you enjoy lukewarm disappointment.

Act 9: Why Aren’t These Everywhere?

At this point you might be wondering:

If we can make fridges for single drinks... why hasn’t Coke just done it?

Good question.

The answer is somewhere between physics, logistics, and economics.

- Space: Most chillers eat into the drink volume or require bulky attachments. Consumers want 330 ml of drink, not 270 ml + 60 ml of engineering.

- Cost: Adding a self-chilling module can double or triple the price of the product.

- Recycling: It’s hard to make a single-use can with multiple materials, pressurized parts, and non-recyclable cartridges.

- Safety: Gas cartridges + flammable refrigerants + pressurized pouches = a lot of liability.

- Timing: Most people don’t mind waiting for their drink to chill. Or, they just bring a cooler.

But here's the twist:

The tech exists. The demos have been made. And the future might be modular:

Clip-on cooling rings.

Dock-style smart beverage stations.

Regenerable sorption sleeves.

Solar-chilling drink stands.

In short: You might not own a self-chilling can — yet — but the tech is chilling in the wings.

Act 10: Which Method Wins?

| Method | Chill Time | Portability | Energy | Weight | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas-expansion | ★★★★★ | ★★★☆☆ | Internal gas | Medium | $$$ |

| Sorption | ★★★☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | Internal water | High | $$ |

| Salt-solution | ★★★☆☆ | ★★☆☆☆ | Internal chem. | High | $ |

| Peltier/TEC | ★★☆☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ | Battery | High | $$ |

| Mini-compressor | ★★★★☆ | ★★★★☆ | Battery/Solar | Medium | $$$ |

| Solar+compressor | ★★★☆☆ | ★★★☆☆ | PV + battery | Medium | $$$$ |

Epilogue: The Cold Future

Self-cooling cans live at the weird crossroads of physics, user expectations, and marketing fairy dust.

They aren’t impossible. Today, only the trade-offs still bite:

- If you go fast, you pay in hardware (pressure, cartridges, heat exchangers).

- If you go safe and simple, you pay in mass (water, salts, sorbents) and single-use waste.

- If you go electric, you pay in power and in “why didn’t I just bring a cooler?”

So when someone asks, “Why can’t they make a can that cools itself?”, the honest answer is:

They can. They did. They’re just waiting for the moment it’s cheaper (and cleaner) than a bag of ice.

And when that moment arrives, the sound of the future probably will be a tiny, satisfying:

PSSHT.

Sources

Carrier, n.d. R744 (CO₂) Temperature–Pressure Chart. Carrier Transicold (Toolbox). https://www.transcentral.carrier.com/cpgtechpubs/toolbox/temp-pressure-chart_r744.html. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

National Refrigerants, 2025. R1234yf Refrigerant Information. National Refrigerants, Inc. https://nationalref.com/r1234yf/. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎ ↩︎

Danfoss, 2024. A2L Refrigerants in Commercial Refrigeration. Danfoss. https://www.danfoss.com/en/about-danfoss/our-businesses/cooling/refrigerants-and-energy-efficiency/a2l-refrigerants-in-commercial-refrigeration/. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎ ↩︎

Packaging Digest / Moylan, C., 2017. Chill-Can presents a new twist in on-demand cold beverages. Packaging Digest. https://www.packagingdigest.com/beverage-packaging/chill-can-presents-a-new-twist-in-on-demand-cold-beverages. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Packaging Digest / Mullen, L., 2018. 7‑Eleven tests self-chilling can for new cold coffee. Packaging Digest. https://www.packagingdigest.com/beverage-packaging/7-eleven-tests-self-chilling-can-for-new-cold-coffee. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Wikipedia, n.d. Water (data page) — heat of vaporization. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_(data_page). Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Michigan Technological University, n.d. Typical values of the convection heat transfer coefficient (from Incropera et al.). https://pages.mtu.edu/~fmorriso/cm3120/typical_values_heat_transfer_coefficient.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Phan, S., Lissoway, J., & Lipman, G.S., 2013. Chemical cold packs may provide insufficient enthalpy change for treatment of hyperthermia. Wilderness & Environmental Medicine 24(1): 37–41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23312558/. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Flinn Scientific, n.d. Making an Instant Cold Pack (ammonium nitrate dissolution is endothermic). https://www.flinnsci.com/globalassets/flinn-scientific/all-free-pdfs/dc0061.00.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Shilpa, M. K., Raheman, M. A., Aabid, A., Baig, M., Veeresha, R. K., & Kudva, N., 2022. A Systematic Review of Thermoelectric Peltier Devices: Applications and Limitations. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing (FDMP). https://www.techscience.com/fdmp/v19n1/49202/html. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Aspen Systems, 2014. Vapor‑Compression vs. Thermoelectric Chillers. Aspen Systems, Inc. https://aspensystems.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Vapor-compression-vs-Thermoelectric-Chillers.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎ ↩︎

Silva‑Romero, R., et al., 2024. A Review of Small‑Scale Vapor Compression Refrigeration Technologies. Applied Sciences 14(7):3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14073069. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Dobos, A.P., 2014. PVWatts Version 5 Manual. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. https://pvwatts.nrel.gov/downloads/pvwattsv5.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎

Fraunhofer ISE, 2025. Photovoltaics Report (commercial module efficiency metrics). https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/de/documents/publications/studies/Photovoltaics-Report.pdf. Accessed 25 January 2026. ↩︎